Literature across languages

- Stone Bridge Press

- Mar 8, 2024

- 4 min read

Part 1: From English to Japanese

It’s easy to take for granted today the porousness of national boundaries and the effortless transmission of culture between languages. If this year you have occasion to read a work of Japanese literature in translation, you might be confirmed in this thought with such a huge variety to choose from. Of course, a century ago the lay reader would have quite the opposite experience, half a century on from Japan’s “opening,” despite the effervescence of Meiji and Taisho literature. What’s obscured in the profusion of foreign-language fiction is that cultural transfer is a material process mediated by politics, people, and, to an extent, chance. In this article I’m looking at the initial transfer of English-language literature into Japanese. Next time, I’ll look at the reverse, when Japanese literature made its to the Anglosphere.

The first translations of Western texts to Japanese occurred on Japanese terms. The Nagasaki trade with the Dutch, and earlier the Portuguese, was tightly regulated (in fact, the official position of interpreter was a hereditary monopoly) and its political imperatives gave priority to medical and scientific learning. To make matters more complicated, the initial works of fiction would have the difficult task of bridging the gap between two symbolic contexts with very little shared history. And besides, Dutch was the exclusive means of communication in the trade until the end of the Edo period and expansion of trade. The proper starting point of English–Japanese literary exchange begins in the Meiji period as Japanese left to be educated in Britain and the United States.

So what were the first works of English fiction to make their way into Japanese? Ignoring partial texts and earlier translation of Robinson Crusoe (from the Dutch edition most likely) dating to the 1850s we arrive at an unexpected starting point. The distinction apparently belongs to Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Ernest Maltravers, translated in 1879 with the title A Spring Tale of Blossoms and Willows. (This claim must have its origins in Basil Hall Chamberlain’s Things Japanese from 1905 in which he calls it “the first European novel to be translated.” However, this seems to be contradicted by the earlier translation of Robinson Crusoe.) On its literary merits alone Ernest Maltravers seems to have outstripped its proper place in the canon. Maybe this this an example of pure historical happenstance or maybe the translator found the work truly exemplary in some important way, as Donald Keene writes of these initial translations:

“Why, for example, was Albinia: or, the Young Mother, published in Baltimore in 1833, preferred to any of the masterpieces of English literature? Perhaps it was the favorite book of the landlady who ran the lodgings where a young Japanese student was learning English; but conceivably the translator thought that this book, better than any other he knew, portrayed the emotional life of the Europeans in a way intelligible to Japanese.”

Likely both valences of this question are true in some respect. The translator found Ernest Maltravers’s Byronic hero and harrowing love story to assert some human truth that was not otherwise clear to the Japanese reader. One finds this broadly true of the early translation, that they served as example. However, one wonders if in the long list of works in English concerned with the tortured emotional lifeworld of their protagonists there wasn't a better choice—what about Hamlet? Of course, Shakespeare’s works wouldn’t have long to wait for translation.

Shakespeare’s first appearance in Japanese would indeed be from Hamlet but, ironically, in a work on non-fiction. Samuel Smile’s Self-Help was very influential in its time (indeed it would seem to have spawned the entire genre) and circulated not just in the English-speaking world but across many languages in the increasingly globalized nineteenth century. The book’s aim was to instruct the reader on how to fashion oneself into the ideal subject of the Victorian era. To this end, great men of art and industry are discussed as examples, Shakespeare among them. It includes a short excerpt from Hamlet that would coincidentally mark the first attempt to render Hamlet into Japanese.

Hamlet’s second appearance would be no less inadvertent. An issue of Japan Punch, an offshoot of the British satirical magazine Punch, featured a translation of Hamlet’s famous “To be, or not to be” soliloquy. The translation was unintelligible. In fact, that was the intent in order to mock a contemporary Japanese language–learning book that, when used to translate the famous speech, produced nonsense.

Another translator of Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Tsubouchi Shoyo (1859–1935), would finally bridge the gap. A major literary critic, novelist, and translator of the period, Tsubouchi’s object in translation was no less pedagogic than his contemporaries. However, Tsubouchi’s intent was literary through and through. He thought that in the literary realm Japan should not just learn about their Western counterparts but learn from them. His theory of the novel, as he stated in the preface to his translation of Bulwer-Lytton’s Rienzi, amounted to a sort of realism:

“A true novelist's skill consists in portraying vividly the state of the seven emotions, observing fully and completely human feelings, leaving nothing out, and in making imaginary characters behave in an imaginary world so convincingly that they seem like real people.”

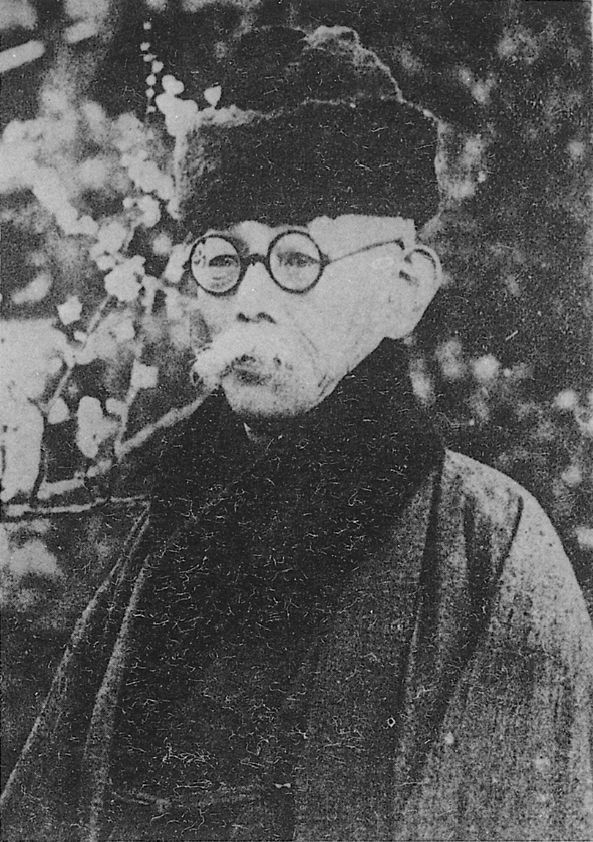

Hamlet by that time had already become a celebrated work in Japan by the twentieth century thanks to decades of adaptations and partial translations by the likes of Tsubouchi, Shimazaki Toson, and Mori Ogai. Tsubouchi set about translating Shakespeare’s entire body of work, and it is Tsubouchi whom we can credit with the first full translation of Hamlet into Japanese. He staged performances of his translation in 1907 and 1911, which would become the touchstone for a generation of Japanese writers, in both praise and critique.

If you’re interested in Japanese literature in translation, Stone Bridge Press has a wide variety to choose from. This includes modern translations of classics such as Osamu Dazai’s A Shameful Life, Kenji Miyazawa’s Milky Way Railroad, and Kansuke Naka’s The Silver Spoon as well as new translation of contemporary Japanese fiction from our MONKEY imprint.